[The following is a guest post from my colleague Richard Sproat. This should go without saying, but: this post does not represent the opinions of anyone’s employer.]

In 2009 a paper appeared in Science by Rajesh Rao and colleagues that claimed to show using “entropic evidence” that the thus far undeciphered Indus Valley symbol system was true writing not, as colleagues and I had argued, a non-linguistic symbol system. Some other papers from Rao and colleagues followed, and there was also a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society by Rob Lee and colleagues that used a different “entropic” method to argue that symbols carved on stones by the Picts of Iron Age Scotland also represented language.

I, and others, were deeply skeptical (see e.g. here) that such methods could distinguish between true writing and symbol systems that, while having structure, encoded some sort of non-linguistic information. This skepticism was fed in part by our observation that completely random meaningless “symbol systems” could be shown to fall into the “linguistic” bin according to those measures. What if anything were such methods telling us about the difference between natural language and other systems that convey meaning? My skepticism led to a sequence of presentations and papers, culminating in this paper in Language, where I tried a variety of statistical methods, including those of the Rao and Lee teams, in an attempt to distinguish between samples of systems that were known to be true writing, and systems known to be non-linguistic. None of these methods really worked and I concluded that simple extrinsic measures based on the distribution of symbols without knowing what the symbols denote, were unlikely to be of much use.

The upshot of this attempt at debunking Rao’s and Lee’s widely publicized work was that I convinced people who were already convinced and failed to convince those who were not. As icing on the cake, I was accused by Rao and Lee and colleagues of totally misrepresenting their work, which I most certainly had not done: indeed I was careful to consider all possible interpretations of their arguments, the problem being that their own interpretations of what they had done seemed to be rather fluid, changing as the criticisms changed; on the latter point see my reply, also in Language. This experience led me to pretty much give up the debunking business entirely, since people usually end up believing what they want to believe, and it is rare for people to admit they were wrong.

Still, there are times when one feels inclined to try to set the record straight, and one such instance is this recent announcement from MIT about work from Regina Barzilay and colleagues that purports to provide a machine-learning based system that “aims to help linguists decipher languages that have been lost to history.” The paper this press release is based on (to appear in the Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics) is of course more reserved than what the MIT public relations people produced, but is still misleading in a number of ways.

Before I get into that though, let me state at the outset that as with the work by Rao et al. and Lee et al. that I had critiqued previously, the issue here is not that Barzilay and colleagues do not have results, but rather what one concludes from their results. And to be fair, this new work is a couple of orders of magnitude more sophisticated than what Rao and his colleagues did.

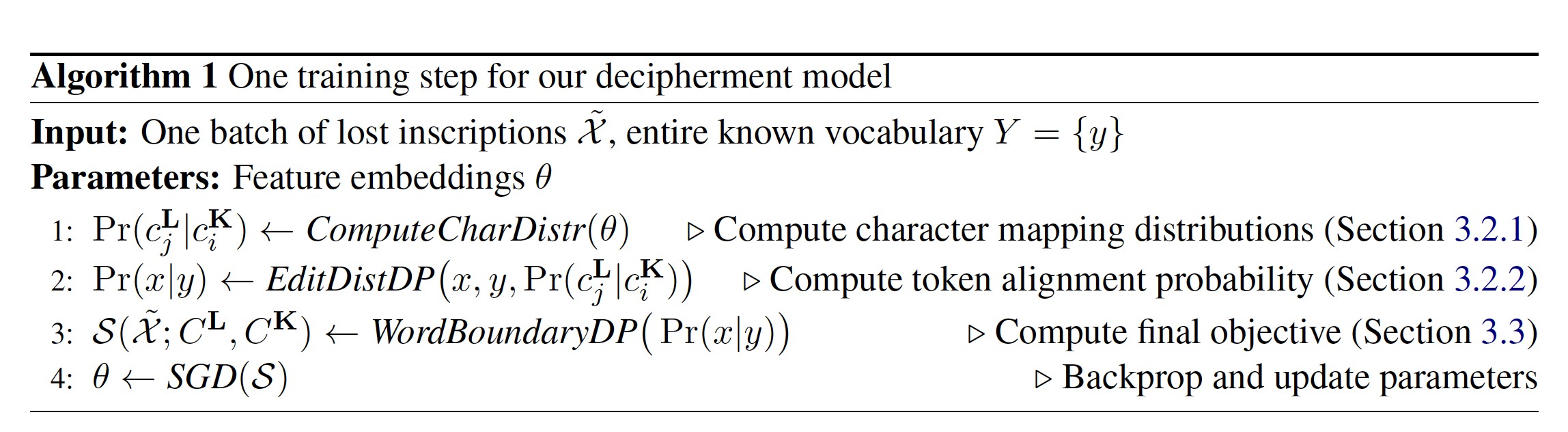

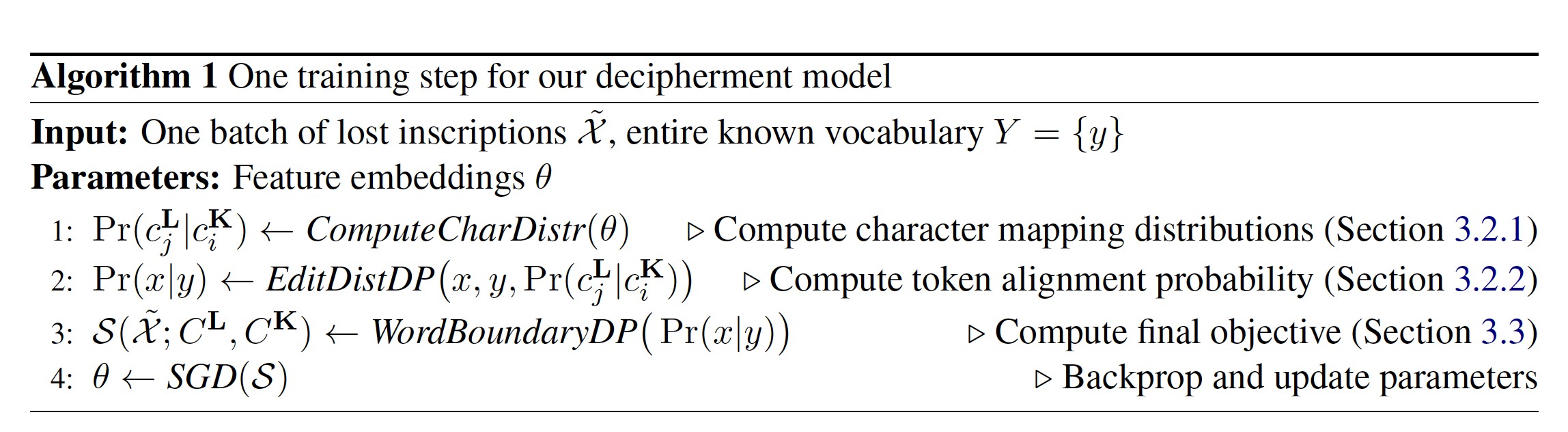

In brief summary, Barzilay et al’s approach is to take a text in an unknown ancient script, which may be unsegmented into words, along with phonetic transcriptions of a known language. In general the phonetic values of the unknown script are, well, not known, so candidate mappings are generated. (The authors also consider cases where some of the values are known, or can be guessed at, e.g. because the glyphs look like glyphs in known scripts.) The weights on the various mappings are learnable parameters, and the learning is also guided by phonological constraints such as assumed regularity of sound changes and rough preservation of the size of the phonemic inventory as languages change. (Of course, phoneme inventories can change a lot in size and details over a long history: Modern English has quite a different inventory from Proto-Indo-European. Still, since one’s best hope of a decipherment is to find languages that are reasonably closely related to the target, the authors’ assumption here may not be unreasonable.) The objective function for the learning aims to cover as much of the unknown text as possible while optimizing the quality of the extracted cognates. Their training is summarized in the following pseudocode from page 6 of their paper:

One can then compare the results of the algorithm when run with the unknown text, and a set of known languages, to see which of the known languages is the best model. The work is thus in many ways similar to earlier work by Kevin Knight and colleagues, which the present paper also cites.

In the experiments the authors used three ancient scripts: Ugaritic (12th century BCE), a close relative of Hebrew; Gothic, a 4th century CE East Germanic language that is also the earliest preserved Germanic tongue; and Iberian, a heretofore undeciphered script — or more accurately a collection of scripts — of the late pre-Common Era from the Iberian peninsula. (It is worth noting that Iberian was very likely to have been a mixed alphabetic-syllabic script, not a purely alphabetic one, which means that one is giving oneself a bit of a leg up if one bases one’s work on a transliteration of those texts into a purely alphabetic form.) The comparison known languages were Proto-Germanic, Old Norse, Old English, Latin, Spanish, Hungarian, Turkish, Basque, Arabic and Hebrew. (I note in passing that Latin and Spanish seem to be assigned by the authors to different language families!)

For Ugaritic, Hebrew came out as dramatically closer than other languages, and for Gothic, Proto-Germanic. For Iberian, no language was a dramatically better match, though Basque did seem to be somewhat closer. As they argue (p. 9):

The picture is quite different for Iberian. No language seems to have a pronounced advantage over others. This seems to accord with the current scholarly understanding that Iberian is a language isolate, with no established kinship with others.

“Scholarly understanding” may be an overstatement since the most one can say at this point is that there is scholarly disagreement on the relationships between the Iberian language(s) and known languages.

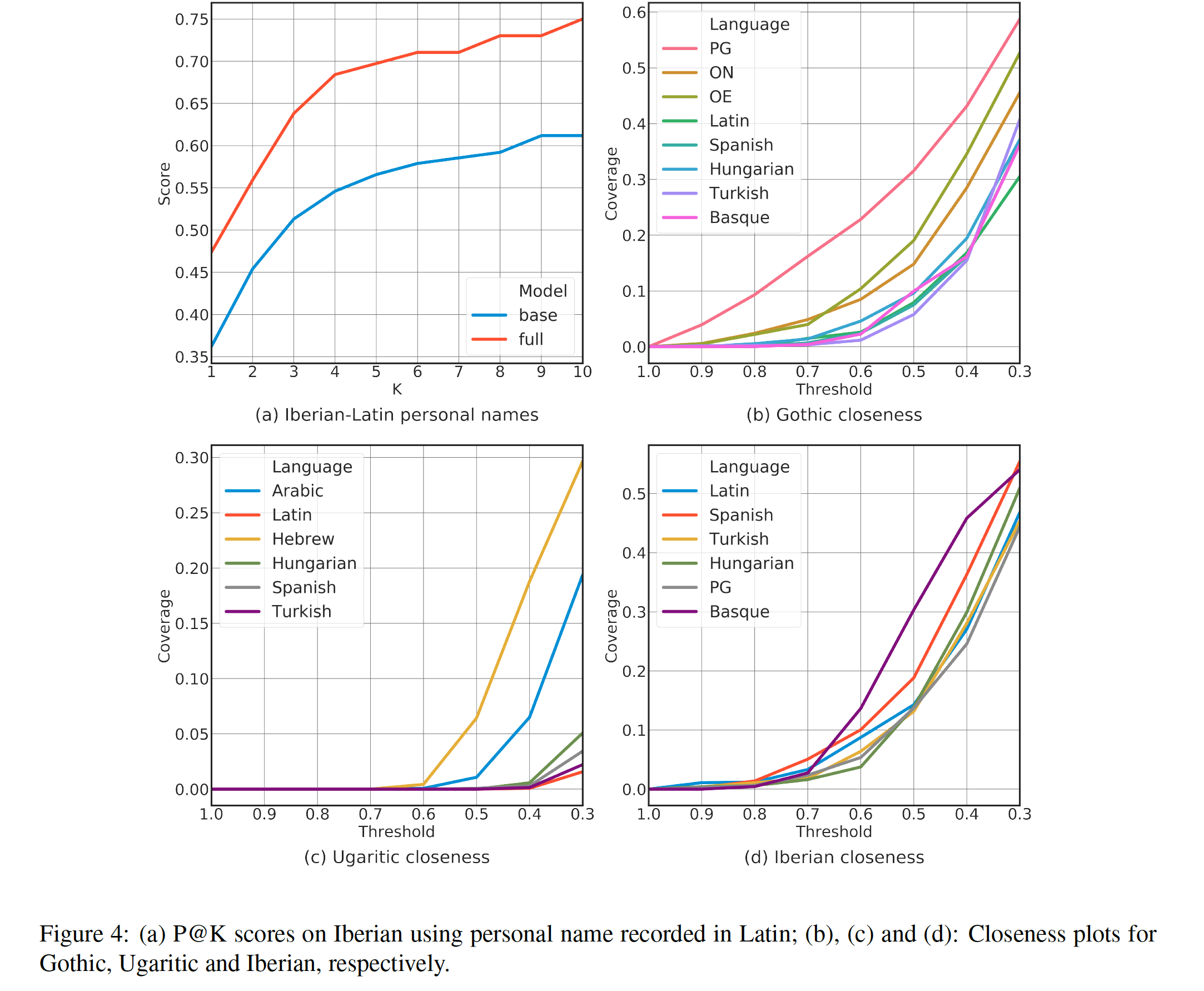

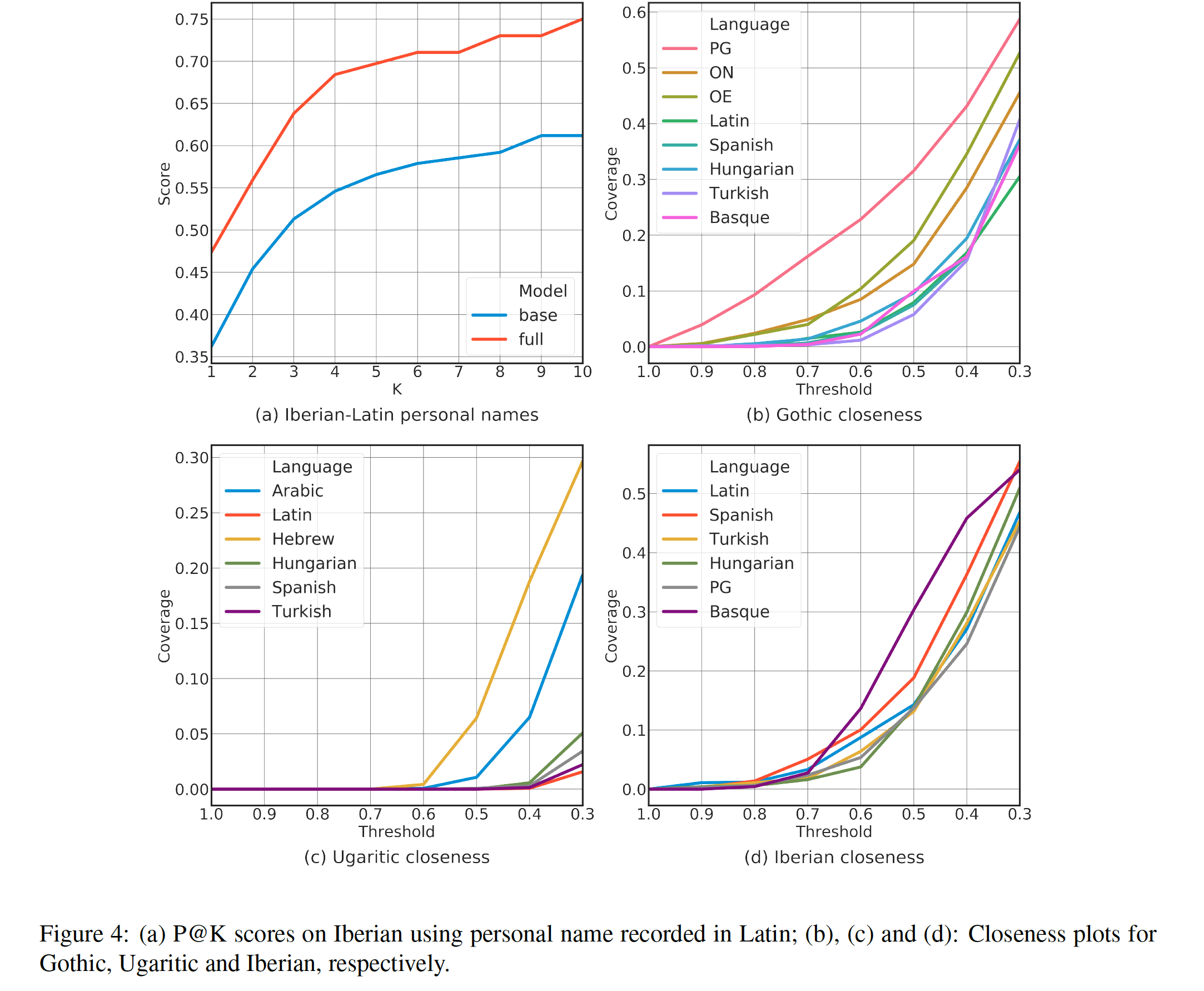

But, in any case, one problem is that since they only perform this experiment for three ancient scripts, two of which they are able to find clear relationships for, and the third not so clearly, it is not obvious what if anything one can conclude from this. The statistical sample is not such as to be overwhelming in its significance. Furthermore, in at least one case there is a serious danger of circularity: the closest match they find for Gothic is with Proto-Germanic, which shows a much better match than the other Germanic languages, Old Norse or Old English. But that is hardly surprising: Proto Germanic reconstructions are heavily informed by Gothic, the earliest recorded example of a Germanic language. Indeed, if Gothic were truly an unknown language, and assuming that we had no access to a reconstructed protolanguage that depends in part on Gothic for its reconstruction, then we would be left with the two known Germanic languages in their set, Old English and Old Norse. This of course would be a more reasonable model in any case for the situation a real decipherer would encounter. But then the situation for Gothic becomes much less clear. Below is their Figure 4, which plots various settings of their coverage threshold hyperparameter rcov against the obtained coverage. The more separated the curve for the language is above the rest, the better the method is able to distinguish the closest matched language from everything else. With this in mind, Hebrew is clearly a lot closer to Ugaritic than anything else. Iberian, as we noted, does not have a language that is obviously closest, though Basque is a contender. For Gothic, Proto-Germanic (PG) is a clear winner, but if one removed that the closest two are now Old English (OE) and Old Norse (ON). Not bad, of course, but just eyeballing the plots, the situation is no longer as dramatic, and not clearly more dramatic than the situation for Iberian.

And as for Iberian, again, they note (p. 9) that “Basque somewhat stands out from the rest, which might be attributed to its similar phonological system with Iberian”. But what are they comparing against? Modern Basque is certainly different from its form 2000+ years ago, and indeed if one buys into recent work by Juliette Blevins, then Ancient Basque was phonologically quite a bit different from the modern language. Which in turn leaves one wondering what these results are telling us.

The abstract of the paper opens with the statement that:

Most undeciphered lost languages exhibit two characteristics that pose significant decipherment challenges: (1) the scripts are not fully segmented into words; (2) the closest known language is not determined.

Of course this is all perfectly true, but it rather understates the case when it comes to the real challenges faced in most cases of decipherment.

To wit:

Not only is the “closest … language” not usually known, but there may not even be a closest language. This appears to be the situation for Linear A where, even though there is a substantial amount of Linear A text, and the syllabary is very similar in appearance and was almost certainly the precursor to the deciphered Linear B, decipherment has remained elusive for 100 years in large measure because we simply do not know anything about the Eteocretan Language. It is also the situation for Etruscan. The authors of course claim their results support this conclusion for Iberian, and thereby imply that their method can help one decide whether there really is a closest language, and thus presumably whether it is worth wasting one’s time pursuing a given relationship. But as we have suggested above, the results seem equivocal on this point.

Even when it turns out that the text is in a language related to a known language, the way in which the script encodes that language may make the correspondences far less transparent than the known systems chosen for this paper. Gothic and Ugaritic are both segmental writing systems which presumably had a fairly straightforward grapheme-to-phoneme relation. And while Ugaritic is a “defective” writing system in that it fails to represent, e.g., most vowels, it is no different from Hebrew or Arabic in that regard. This makes it a great deal easier to find correspondences than, say, Linear B. Linear B was a syllabary, and it was a lousy way to write Greek. It failed to make important phonemic distinctions that Greek had, so that whereas Greek had a three-way voiced-voiceless-voiceless aspirate distinction in stops, Linear B for the most part could only represent place, not manner of articulation. It could not for the most part directly represent consonant clusters so that either these had to be broken up into CV units (e.g. knossos as ko-no-so) or some of the consonants ended up being unrepresented (e.g. sperma as pe-ma).

And all of this assumes the script was purely phonographic. Many ancient scripts, and all of the original independently invented scripts, included at least some amount of purely logographic (or, if you prefer, morphographic) and even semasiographic symbology, so that an ancient text was a mix of glyphs, some of which would relate to the sound, and others of which would relate to a particular morpheme or its meaning. And when sound was encoded, it was often quite unsystematic in the way in which it was encoded, certainly much less systematic than Gothic or Ugaritic were.

Then there is the issue of the amount of text available, which may be merely in the hundreds, or fewer, of tokens. And of course there are issues familiar in decipherment such as knowing when two glyphs in a pair of inscriptions that look similar to each other are indeed the same glyph, or not. Or as in the case of Mayan, where very different looking glyphs are actually calligraphic variants of the same glyph (see e.g. here in the section on “head glyphs”). The point here is that one often cannot be sure whether two glyphs in a corpus are instances of the same glyph, or not, until one has a better understanding of the whole system.

Of course, all of these might be addressed using computational methods as we gradually whittle away at the bigger problem. But it is important to stress that methods such as the one presented in this paper are really a very small piece in the overall task of decipherment.

We do need to say one more thing here about Linear B, since the authors of this paper claim that one of their previously reported systems (Luo, Cao and Barzilay, 2019) “can successfully decipher lost languages like … Linear B”. But if you look at what was done in that paper, they took a lexicon of Linear B words, and aligned them successfully to a nicely cleaned up lexicon of known Greek names noting, somewhat obliquely, that location names were important in the successful decipherment of Linear B. That is true, of course, but then again it wasn’t particularly the largely non-Greek Cretan place names that led to the realization that Linear B was Greek. One must remember that Michael Ventris, no doubt under the influence of Arthur Evans, was initially of the opinion that Linear B could not be Greek. It was only when the language that he was uncovering started to look more and more familiar, and clearly Greek words like ko-wo (korwos) ‘boy’ and i-qo (iqqos) ‘horse’ started to appear that the conclusion became inescapable. To simulate some of the steps that Ventris went through, one could imagine using something like the Luo et al. approach as follows. First guess that there might be proper names mentioned in the corpus, then use their algorithm to derive a set of possible phonetic values for the Linear B symbols, some of which would probably be close to being correct. Then use those along with something along the lines of what is presented in the newest paper to attempt to find the closest language from a set of candidates including Greek, and thereby hope one can extend the coverage. That would be an interesting program to pursue, but there is much that would need to be done to make it actually work, especially if we intend an honest experiment where we make as few assumptions as possible about what we know about the language encoded by the system. And, of course more generally this approach would fail entirely if the language were not related to any known language. In that case one would end up with a set of things that one could probably read, such as place names, and not much else — a situation not too dissimilar from that of Linear A. All of which is to say that what Luo et al. presented is interesting, but hardly counts as a “decipherment” of Linear B.

Of course Champollion is often credited with being the decipherer of Egyptian, whereas a more accurate characterization would be to say that he provided the crucial key to a process that unfolded over the ensuing century. (In contrast, Linear B was to a large extent deciphered within Ventris’ rather short lifetime — but then again Linear B is a much less complicated writing system than Egyptian.) If one were being charitable, then, one might compare Luo et al.’s results to those of Champollion, but then it is worth remembering that from that initial stage to a full decipherment of the system can still be a daunting task.

In summary, I think there are contributions in this work, and there would be no problem if it were presented as a method that provides a piece of what one would need in one’s toolkit if one wanted to (semi-) automate the process of decipherment. (In fact, computational methods have played thus far only a very minor role in real decipherment work, but one can hold out hope that they could be used more.) But everything apparently has to be hyped these days well beyond what the work actually does.

Needless to say, the press loves this sort of stuff, but are scientists mainly in the business of feeding exciting tidbits to the press? Apparently they often are: my paper that I referenced in the introduction that appeared in Language was initially submitted to Science as a reply to the paper by Rao and colleagues. This reply was rejected before it even made it out of the editorial office. The reason was pretty transparent: Rao and colleagues’ original paper purported to be a sexy “AI”-based approach that supposedly told us something interesting about an ancient civilization. My paper was a more mundane contribution showing that none of the proposed methods worked. Which one sells more copies?

In any event, with respect to the paper currently under discussion, hopefully my attempt here will have served at least to put things a bit more in perspective.

Acknowledgements: I thank Kyle Gorman and Alexander Gutkin for comments on earlier versions.