How many Optimality Theory (OT) grammars are there? I will assume first off that Con, the constraint set, is fixed and finite. I make this assumption because it is one assumed by nearly all work on the mathematical properties of OT. Given the many unsolved problems in OT learning, joint learning of constraints and rankings seems to add unnecessary additional complexity.1 So we suppose that there are a finite set of constraints, and let $n$ be the cardinality of that set. If we put aside for now the contents of the lexicon (i.e., the set of URs), one can ask how many possible constraint rankings there are as a function of $n$.

Prince & Smolensky (1993), in their “founding document”, seem to argue that constraint rankings are total. Consider the following from a footnote:

With a grammar defined as a total ranking of the constraint set, the underlying hypothesis is that there is some total ranking which works; there could be (and typically will be) several, because a total ranking will often impose noncrucial domination relations (noncrucial in the sense that either order will work). It is entirely conceivable that the grammar should recognize nonranking of pairs of constraints, but this opens up the possibility of crucial nonranking (neither can dominate the other; both rankings are allowed), for which we have not yet found evidence. Given present understanding, we accept the hypothesis that there is a total order of domination on the constraint set; that is, that all nonrankings are noncrucial.

So it seems like they treat strict ranking as a working hypothesis. This is also reflected in the name of their method factorial typology, because there are $n!$ strict rankings of $n$ constraints. Roughly, they propose that one generate all possible rankings of a series of possible constraints, and compare their extension to typological information.2 In practice, as they acknowledge, OT grammars—by which I mean theories of i-languages presented in the OT literature—contain many cases where two constraints $c, d$ need not be ranked with respect to each other. For example, the first chapter of Kager’s (1999) widely used OT textbook includes a “factorial typology” (p. 36, his ex. 53) in which some constraints are not strictly ranked, and this is followed by a number of tableaux in which he uses a dashed vertical line to indicate non-ranking.3

Prince & Smolensky also acknowledge the existence of cases where there is no evidence with which to rank $c$ versus $d$. The situation is important because any learning algorithm which was trying to enforce a strict ranking of constraints would have to resort to a coin flip or some other unprivileged mechanism to finalize the ranking. Such algorithms are in principle possible to imagine, but neither the final step nor the postulate are motivated in the first place.

Prince & Smolensky finally admit the possibility of what they call crucial non-ranking, cases where leaving $c$ and $d$ mutually unranked has the right extension, but $c lt d$ and $d lt c$ both have the wrong extension.4 Such would constitute the strongest evidence for viewing OT grammars as weakly ranked, particularly if such grammars are linguistically interesting.

I will adopt the hypothesis of weak ranking; it seems unavoidable if only as a matter of acquisition. If one does, the set of possible rankings is actually much larger than $n!$. For example, for the empty set and singleton sets, there is but one weak ranking. For sets of size 2, there are 3: ${a lt b; b lt a; a, b}$. And, at the risk of being pedantic, for sets of size 3 there are 13:

- $a \lt b \lt c$

- $a \lt b, c$

- $a \lt c \lt b$

- $a, b\lt c$

- $a, b, c$

- $a, c \lt b$

- $b \lt a \lt c$

- $b \lt a, c$

- $b \lt c \lt a$

- $b, c \lt a$

- $c \lt a \lt b$

- $c \lt a, b$

- $c \lt b \lt a$

Already one can see that this is growing faster than $n!$ since $3! = 6$.

It is not all that hard to figure out what the cardinality function is here. Indeed, I think Charles Yang (h/t) showed this to me many years ago, and though I lost my notes and had to re-derive it, I’m reasonably sure he came up with is the same solution that I do here. This sequence is known as A000670 and has the formula

$$a(n) = \sum_{k = 0}^n k! S(n, k)$$

where $S$ is the Stirling number of the second kind. Expanding that further we obtain:

$$a(n) = \sum_{k = 0}^n k! \sum_{i = 0}^k \frac{(-1)^{k – i}i^n}{(k – i)!i!} .$$

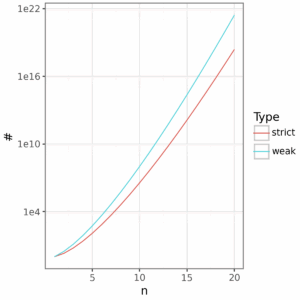

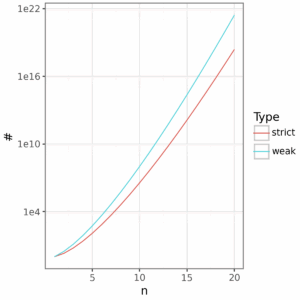

This is a lot of grammars by any account. With just 10 constraints, we are already in the billions, and with 20 it’s between 2 and 3 sextillion. Yet this doesn’t look all that dramatically different than strict ranking when plot in log scale.

Clearly this is essentially infinite in the terminology of Gallistel and King (2009), and this ability to generate such combinatoric possibilities from a small inventory of primitive objects and operations is something that has long been recognized as a desirable element of cognitive theories. Of course, many of these weak rankings will be extensionally equivalent, and even others, I hypothesize, will probably be extensionally non-equivalent but extensionally equivalent with respect to some lexicon. None of this is unique to OT: it’s just good cognitive science.

Endnotes

- Note that the constraint induction of Hayes & Wilson (2008), for example, only considers a finite set thereof and therefore there does exist some finite set for their approach. The same is probably true of approaches with constraint conjunction so long as there are some reasonable bounds.

- Exactly how the analyst is supposed to use this comparison is a little unclear to me, but presumably one can eyeball it to determine if the typological fit is satisfactory or not.

- As far as I can tell, he never explains this notation.

- There is a tradition of using $\ll$ for OT constraint ranking but I’ll put it aside because $\lt$ is perfectly adequate and is the operator used in order theory.

References

Gallistel, C. Randy and King, A. P. 2009. Memory and the Computational Brain: Why Cognitive Science Will Transform Neuroscience. Wiley-Blackwell.

Hayes, B. and Wilson, C. 2008. A maximum entropy model of phonotactics and phonotactic learning. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 397-440.

Prince, A., and Smolensky, P. 1993. Optimality Theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. Rutgers Center for Cognitive Science Technical Report TR-2.